This post will look much better viewed in a browser, on a larger screen. Give it a try.

By the second week, everyone was capable of basic sharpening, chiseling, planing, and joining wood.

We outsiders also reached a less offensive and rudimentary harmony with the practices of the temple.

Now, the students were ready to begin working on the frame. As much as people with one week of experience could be.

The frame was meant to be a gift to my partner, to house her ceramics wheel and kiln. As that relationship gently ran its course over the last year, the frame became a frame for the sake of this class.

I privately found myself putting my feelings of loss into my work; Into my sharpening, my refinement of my tools, my sawing and chiseling and planing. Sometimes, it was as fuel, sometimes as a distraction; it was a matter of returning to my senses and getting back to work before I was injured or damaged some work pieces.

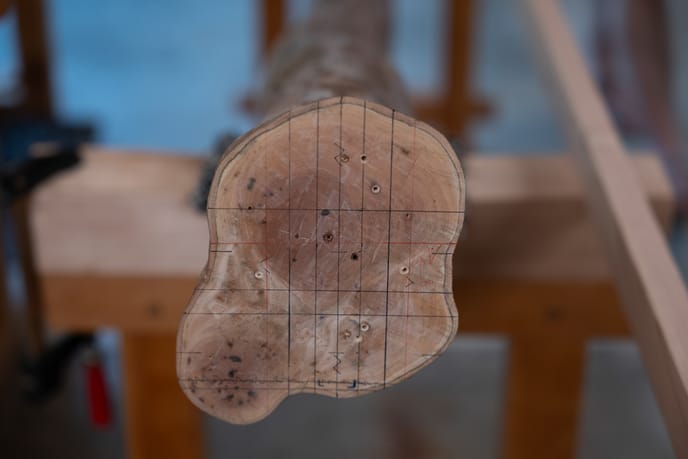

The frame’s structure stood on nine posts, ishibatate style, where the posts rest on stone bases.

Custom poured concrete footings with through bolts were used. Since the structure is open-walled, I wasn’t worried about lift from hurricanes, so there were no plans to link the footings to the ground below.

At the structure’s opening, we placed the two most beautiful and stable posts we could find, joined across the top by our natural beam. Above the natural beam was a small riser post, a tsuka, and a small cross beam to support the taller part of the roof. Above everything were three long beams which would support the rafters.

Ishiibatate-style buildings can’t just plug the posts into a mudsill (a beam that sits on a foundation). So the joinery for the lowest beams is more complicated than a simple mortise and tenon. Some of the tenons were drawn either oak pegged (at the corners or tops of posts). Or, drawn with a shachi joint using a floating oak tenon and some wedges into mortises on the beams.

It was a lot of work. So Jason opted to use production-minded professional practices over hand cutting of joints to get things done quickly. We did a lot of practice mortises by hand, but none for the frame. Tenons were sawn by hand, mostly.