Happy New Years. I took a week off and it nearly drove me crazy. What is it about rest that is so violent to people who are busy? It's something to think about. But not too long, because there are a lot of things that need to be built. And building is more fun than thinking.

First, an update on the class prep. You could not imagine a more hostile place to try to practice japanese carpentry than Honolulu. Specifically, I am referring to locating suitable species and grade of lumber here. We might need to experiment more with local sugi (big island) and eucalyptus but I hear only discouraging things about these trees in practice. We will have to see. Maybe there's a hoard of old growth redwood reclaimed from water towers for us, but that stuff is not inexpensive. Invasives we know of are not resistant enough to weather or pests. For now, we are looking outward for our material.

Last week, we finally found a good last minute supplier for our Port Orford Cedar for the Chozen-ji project. After determining no one on island would be able to supply anything close to what we needed, in the time frame we needed it in, we found Matt at Metcalf in Oregon. He had great prices and grades and we choose a grade with hard knots to save money and give the students some knots to deal with, as well as less pressure to do perfect work on perfect wood. For a shed type structure, it will be fine, but Matt double checked this grade would be good enough for our work. Lucas Benjamin and Yann both pointed me his way and I had to thank him for his caring attitude during the process. There is a point where a craftsperson is experienced enough to do the job well, but still establishing themselves to the point they will deal with smaller customers. I am grateful for his existence and what that means to do this kind of building in America.

On island, my friend Keola, who is serious enough about forestry to train on the mainland, helped us track down a strawberry guava log suitable for the class project's natural beam. We got it from a homeowner's property in Manoa, and some monks helped us haul it back to the temple where we seasoned it with some borate. Like a lot of fruit wood, it isn't exactly resistant to bugs (at all) and borate is part of the long term fix. The wood, when finished, is more uniform but not dissimilar to cherry in feel. Possibly a little softer. It's not often used for fine work, but I think it has potential. It's also an invasive species and culling it is welcomed, culturally. It also happens to be a beautiful tree, and commonly used in japanese-esque landscaping here. I have a few at our house.

The log wasn't large but it also wasn't something one person could deal with. At one point, unloading the log, it tumbled to the gravel behind the workshop at the temple. It's just a part of being interested in this kind of work but I find myself always wishing for a larger truck and shop at times like this. And more friends interested in this kind of work, on island. Strong, crazy friends. I guess that's why we have Jason coming out. And others we have planned.

Class is almost full. Watching the temple staff vet the personalties of the students to make sure they will handle the zen training well is something I don't think any carpentry class has had. But I do know on small builds, some teachers are doing the same kind of vetting. Carpentry is a team sport, which is part of why I do it, since I am not always good at depending on other people. It's good practice for me to also live up to the expectations of others, these days.

Lastly, we have a pile of cedar 4x4s from Lowes that are to be made into sawhorses. They will stay at the temple long after the class is done. Maybe one day they can be used to build structures for the grounds, so we are making them ready for larger structural members. We will be using Jason's specs for this set, rather than the kind that I developed studying Yann and Dale's.

Onto this ridiculous dog step.

A part of my dream of becoming a better craftsperson is to increase the service I can provide for my friends and community. This is the thinking behind trying to build faster--not to mention teachers constantly setting the example of working faster themselves. Of course, you have to work perfectly as possible and as fast as possible. So, one is constantly being berated for one or the other, in an ideal learning environment.

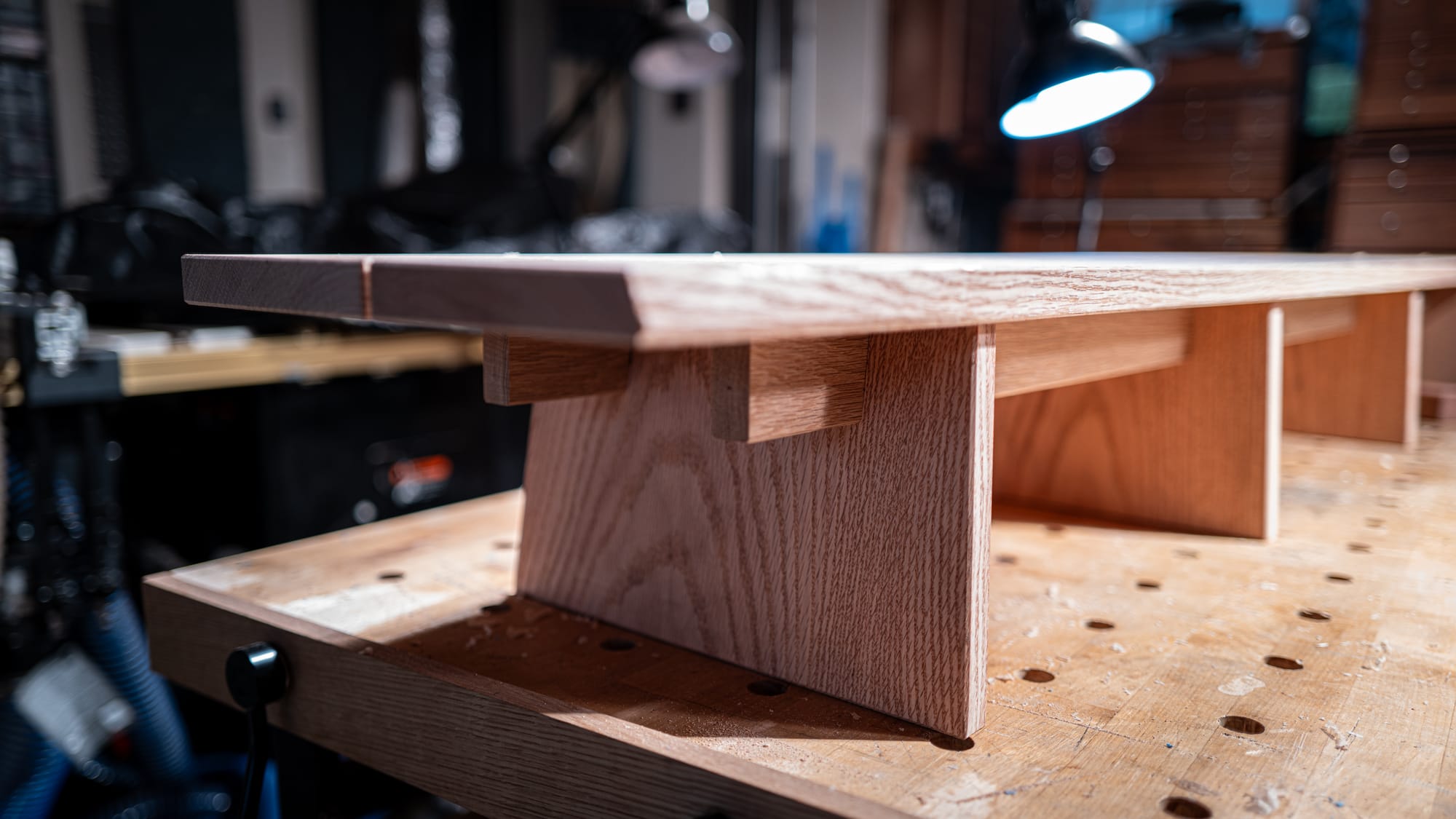

My friends have an old Shiba Inu. They have been waiting for me to build a platform for their aging dogs to use to climb into their bed. The dog looks about 20 pounds. But I felt that I had to make a bench type structure that supported over 500 pounds, to be safe. That's because my friends are 200 and 240 pounds respectively, and if you add in the extra forces from stepping up and down to the bench, I felt uncomfortable making something of average strength.

Overbuilding is frowned upon in furniture building, but for someone with my tendency to over do things because of concern and lack of experience, it's a thing I like to do. It's also because of the feelings of safety one gets from stouter timber frame carpentry design languages. So I don't mind going really crazy on strength. I had a wide board of red oak and some white oak scraps that I thought would be good material for this project and too coarse for other things.

The stuff was only an inch thick, and quite warped, so I knew I would be lucky to get 7/8ths out of it after milling. By cutting things shorter, and cutting out the most awkward twists, I did achieve that thickness. As usual, avoiding anything that is dimensionally similar to plywood is important for not just building methods in this type of work, but to let people know that these things are not made of ply.

If I had 8/4 material, I would have done 4 compound angled legs and plenty of stretchers. But, to gain strength from relatively thin material, I added some extra legs, kept the legs as boards, and added two relatively tall stretchers/aprons below each of the two tops. The top was joined by 16 tenons, 8 of which were angled 5 degrees in. The trigonometry on an 8-inch leg angled 5 degrees is like nothing, so things just had to be a millimeter longer on that end to account for final angled feet and tenons. I tend to use an app called trig solver for this kind of situation. Trig solver tells me that an 8 degree leg angled 5 degrees ends up being 8.03 inches, or about 1/64th longer.

No big deal at this length of material.

Mortises were drilled out, cut by hand using HSS timber chisels (real bangers, those things) and a heavy hammer. Angled mortises were done by connecting the top and bottom lines and keeping an eye on the layout line on the edge of the board. Not too bad.

Tenons were really long, with 1/8th inch shoulders on the straight legs, so I tried a rocker tenoning jig. It was terribly inaccurately and sloppy for a 12 inch long shoulder. Tak san would have made this cut on a table saw, with a tall fence. I'll probably build a tall fence as well, for this purpose. The bandsaw was used to cut the shorter dimension of the leg tenons, and since there were 8 identical cuts per leg, 32 total, just reusing the fence position for each of them, saved a lot of time in layout.

The angled legs needed to be chiseled out to the shoulder line, which I did by eye using layout lines on the edge.

The stretchers were notched 1/3rd of its height to preserve strength and the legs were notched to accept the stretchers. The angled legs needed to be done with angled end grain for fit and support.

Before assembly, the angle legs were trimmed, and everything was chamfered and refinished. Each of the legs were given a 5 degree angle on the outer edges to mimic a compound angle leg structure without really doing any compound angle construction. Quick and dirty.

Assembling the angled legs, since in conflict, required the stretchers and straight legs to be placed in first, and then the outer legs placed into the stretcher and top one at a time. Everything was glued together with Titebond ii extend, because I am terrible at glue ups, because I rarely use glue.

I used a HSS plane to shape out rough wood on the outer corners of the room-facing side of the bench, and the bed side was shaped into a small crescent to remove some splintery sap wood.

After that, I gave it a basic finish plane, but nothing too crazy as the mortises and legs had tensioned some of the flatness out of the top boards, making a more pristine finish difficult.

A electric branding iron was tested for the first time, in an inconspicuous location.

A few of the mortise were chipped out from rushing from one side, and one of the tenons needed to be patched because I glanced it with a band saw blade. I probably could have done some thing more ornamental to the ends of the stretchers, even though they will be invisible most of the time.

I told Michael, head priest at Chozen-ji, I realized the last half dozen mistakes I had made had occurred when I was distracted by a similar thought: That this practice I was getting would one day make me a good craftsman. He responded by telling me the most dangerous moment in kendo is the moment after you score a point, if you dwell on it.

Jumping up and down on the modest bench, I felt it would meet the full force of my friends, without flinching.

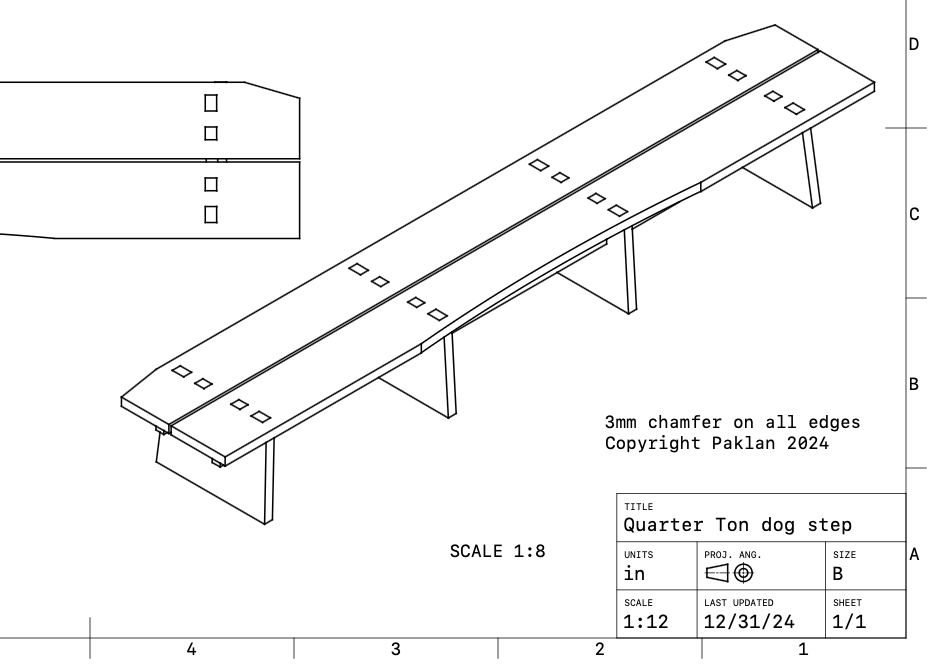

This piece was built without plans, but here are some thrown together from memory, in case anyone is interested in understanding the structure more: