TLDR: Learning craft did something magical for my brain and feelings towards work and life. And since this project is about supporting and creating more craftspeople, I am happy to have put together this resource page for people interested in starting out in Japanese woodcraft. Most 2025 class schedules for my favorite woodworking teachers and friends are online.

A few years ago, during COVID, I was on the board of Kezuroukai USA and trying to get a class video rental program started. In the end, the project was cancelled in favor of focusing on in person events and learning. I didn’t agree with the decision at the time, but In hindsight I understand their point. I believe video learning has a lot of potential with the right teachers but nothing will replace learning in person, where all the senses can be fully engaged.

Jon Stollenmeyer of Somakosha stopped in Honolulu last week on his way back to Japan after the holidays. I wanted him to meet Michael at Chozen-ji and talk about the temple grounds and buildings, in case there is a project 0r classes we can work on together.

Unexpectedly, as soon as we got to my shop, Jon started giving me direct feedback on my tools and planing technique. You can imagine the kind of things he noticed as the American who has spent more time working in Japan as a carpenter than anyone else I can think of.

Jon’s career has been split between both Nakamura Sotoji Komuten, and Somakosha where he works with Yama-san and their team. I have written about Nakamura Satoji Komuten as the place where I first laid eyes on Japanese carpentry, and met Jon’s first boss, Yoshiaki Nakamura. The NYT has written about this firm as such:

"My father hired the master carpenter with the reputation of being No. 1 in Kyoto who specialized in the traditional tea house design,” said Mr. Yabumoto. “His name was Mr. Sotoji Nakamura, and the name is now a brand continued by his son.”

Until his death in 1997, Sotoji Nakamura was known for his work on tea house, or sukiya, designs. His credits include building tea rooms for two Rockefellers, including one at Nelson A. Rockefeller’s home in Pocantico Hills, N.Y., and at a city park in Munich.

Nakamura’s son, Yoshiaki, who now runs the family business, says his father’s most important work was his commission for the tea rooms at the Ise Shrine, the Shinto temple complex about two hours from Kyoto. Since Nakamura’s death, the company has handled projects such as the tea room at the Huntington library and gardens in San Marino, Calif., and the Edo Koji shopping alley at Haneda International Airport in Tokyo."

Jon's feedback was metabolized in any form. If he thought something I did was good, it was good to hear. If he thought something I was doing was ineffective or even terrible, it was good to hear. I was grateful to hear anything that would help me grow or to know I was headed in the right direction. I have no idea why this feeling exists in me, I just know that after 5 years, it’s only getting stronger. It probably has to do with just how hard it is to learn on island, and how difficult it is to travel to study. (Ask me anything about traveling with tools, stones, cameras and a toddler, all at once.)

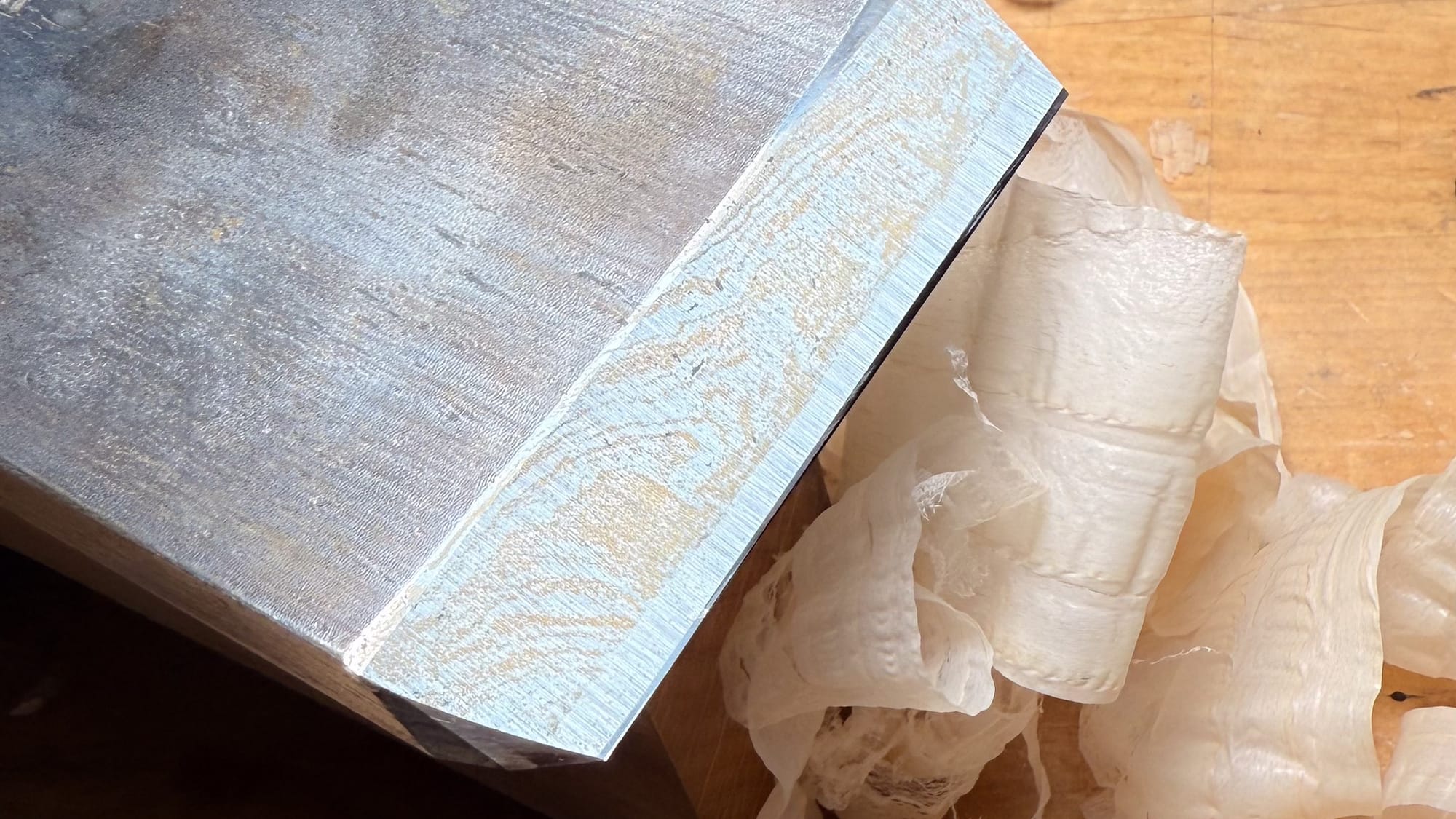

For example, the way Jon uses a kanna is different from anything I’ve ever seen. I can’t explain everything because it’s not my knowledge to share, and I don’t understand everything well enough. But I got to see the sharpening method Somakosha developed in house that uses a deep hollow grind, two stones, including one final stone coated in 20k alumina powder of just the right consistency, and extremely small contact points requiring the balancing of the blade on the very edge, with no other contact on the bevel. (That is, in bicycle terminology, an endo.)

Within 2 minutes, I am getting blades sharper than ever.

(Jon Billing wrote about a version of this way of sharpening a few years ago, which I found effective. But this updated version, showed to me in person where I could observe more nuance and get more feed back, works even better for me.)

Jon's visit also answered a 2 year old question raised by his partner, Yama-san, when I studied under him in Idaho. Yama-san began to tell me about a method of supporting the dai on the work piece, that he described as "crazy", before he decided that he couldn't explain the method well enough to me. At first he said he didn't have the vocabulary in English but the next day I asked him if he just didn't want to confuse me at the level I was at. He nodded.

Asking Jon about this method, he answered by showing me how he likes to provide contact around the entire mouth. This was something he learned from his bosses at Nakamura. But I was told this way is used by some of the highest-end firms to control tear out on the finest work. It also is something I have not seen others in America practice. Again, I'm being a little vague--if you want to learn, you need to study with Jon and Yama-san and ask them directly.

Overall, this is a unique, rare and advanced take on setting up a plane specifically for the pace and quality of work done at Somakosha. And it is incredibly exciting to see craft and tradition grounded in over a thousand years of tricks and methods passed down from master to apprentice, but also expanding, live and in the present.

In a few short minutes, I learned something I could not learn from 10 years on my own–or 10000 years on Youtube. And we're not even getting into architecture or building or design or joinery, yet. Jon said, “thought I could come to Japan for 3-5 years and learn a lot of what I needed to know, now im 15 years in and I feel like I need the rest of my life to really get anywhere with it.“

My point is, to learn from someone who knows, in person, is fast, efficient and beautiful.

It would be worth your time to visit their school, or any school by professionals. I am signed up for 6 weeks of classes, in May, June and July, with them, along with some sessions with Mount Fuji Wood Culture Society, in 2025. (If you sign up for any programs at these places, please drop me a line.)

If you are starting out, I recommend starting with a teacher in your region to learn fundamentals of joints, tools and sharpening. There are teachers like Yann and Dale in the Ashland and Seattle, Jason Fox in Maine, Ziggy in Kentucky, Alfred in France. For those who know they are going to continue on, there is Japan, waiting for us.

One beautiful part of this culture is the emphasis on observation and modeling, and doing, and less on asking or hearing.

I would also warn against learning from people on facebook or youtube without asking them how they know what they are trying to teach you. The advice on these platforms is sometimes a little short on context. So far.

Peers are also amazing for encouragement and sharing of lessons without annoying the boss. Aside from craft being alive, Jon also believes in not trying to learn alone. “When I find people who try to do everything alone, I feel a little bit of sadness because there is no need to and it's a bit slower route. And we can all be partners in learning this stuff. But yeah I mean, it's so deep, and im constantly feeling lucky to have Yamamoto with me.

Jon and I talked about openmindedness when learning. I find it curious how many people doing this work outside of Japan refuse to acknowledge developments in technique and tooling, like use of heavy alloys and diamond resins and grinders to help them do better work, faster for the sake of clients and their families alike. “The best carpenters do fast and beautiful work,” said Jon. He continued, “At Nakamura, I met all these aboslutely incredible carpenters who were excellent at what they do in various ways, but also open to learning, even people who were in their 50 snd 60s who had done amazing things in there career and they still had that curiosity. And hopefully we can learn that forward. ”

In the end, at some point, if you really want to learn this, some feel that apprenticeships and actual work are the only way. I noticed that for people who took this route, there was an initial risk of being annoying by asking too many questions or being around long enough to be first noticed and allowed to be around as an irritation. And then perhaps be ready and given the opportunity to do some real work. And over time, to be less of a burden and annoyance to your bosses. Of course, this is just second hand information, as someone who has never done professional work for a professional for any great amount of time. But it is what I have noticed in a number of professionals, including Jon, who was told he would never be hired at Nakamura, but showed up every day for months on end to help out, regardless of the futility of it.

For the rest of us who can’t take that route, there are still ways to fight to learn and practice and build, even if they are not as straight forward.

For now, go get a lesson from someone who knows.

For members only, a tool for sale that I used on the koi pond project: